Rural – Jersey Country Life Magazine

What’s for Dinner?

Introduction

The Macro Themes

Farming – What Sort?

Something To Eat

Food and Farming in Jersey – New Models

The Natural Environment

Postscript to ‘What’s for Dinner?’

Land For People,

Farmers And Communities

Capturing land value for the common good – by Martin Large

As Mark Twain once said, ‘The trouble with land, they are not making it anymore.’Jersey faces multiple challenges: finite land, rising inequality, the ever-mounting cost of renting or buying a home, the disparity between wealthy retirees and second homers on the one hand and on the other many local families working hard to survive, the needs of entrant farmers for affordable land and, not least, the need for climate adaptation.

Understanding the ways land is owned is vital for a healthy democracy. Who benefits from land ownership? How do planning decisions capture uplift value for private profit rather than for enduring community benefit? For example, a UK council granting planning permission to build houses on agricultural land costing £10,000 an acre can increase the land value many times, resulting in higher house prices and rents.

On a recent visit to Jersey to give a talk hosted by RURAL magazine on the subject of ‘Land for People, Farms and Communities’, I was struck by the range of local people’s observations on local land issues. Entrant young farmers found it hard to lease affordable land to get started, so some went abroad. The average three-bedroom house cost £600,000. Indeed, in May 2019 the Jersey Evening Post reported that the average cost of a Jersey home was twice the UK average and similar to London prices.

There was a debate advocating that landlords should be able to require tenant farmers to manage their land according to high environmental standards. Recently the States of Jersey sold off some publicly owned farmland to the National Trust for Jersey, which was helped by donors. A politician commented that when such land was sold, there should be a maximum return to the public He did not clarify if that ‘return’ was just the highest price, or included a range of environmental, economic, social, access, cultural benefits and addressed government policies, such as food security, jobs or biodiversity.

I found on my visit that if you ask a group of Jersey people what the issues are that affect housing, planning, public spaces or farming you will soon get a rich picture of the land question and good solutions.

When on recent lecture tours in New Zealand, Australia or the USA, I found that similar issues to Jersey’s came up, especially in resort towns. Indeed, despite NZ being much bigger than the UK, with a much smaller population, house prices in Auckland are sky high. The common driver is the British system of land ownership and planning. In Germany, for example, the land system is very different and houses are much cheaper to rent. So, we need to think about land very differently so as to make the most of our land for individual and community benefit.

This article will first describe some examples of how we in Stroud, Gloucestershire, got active with land, farming, food and housing questions and developed some replicable local solutions. Some solutions went national, even getting Community Land Trusts defined in a Housing Act. Secondly, the causes of ever higher land prices will be analysed, and the alternative of commons thinking described, concerning ‘land’ as a bundle of rights. Thirdly, I shall ask: ‘How can a Land for the Many’ system work, using the latest thinking. Finally, how does this thinking benefit Jersey and the next steps?

To begin, here are some examples that might be of interest:

*A group of us facilitated a community plan for the then run-down Stroud’s most desirable future, engaging over 1,000 people over a year. Some of us then formed ‘Stroud Common Wealth’ in 1999 to enable social business and co-operative development, and community asset development, such as raising money from gifts and loans for buying an old church and converting it into The ‘SPACE’- Stroud Performing Arts Centre. Housing was a big issue, so we ran a Land for People conference in 2002 which was a surprise sell out. Looking for co-operative working examples, I got a Winston Churchill Travelling Scholarship to research Community Land Trusts (CLTs) for housing and farming in the USA. A CLT is a charitable, democratic, open membership co-operative body that serves a locality by securing land for leasing for affordable housing, community amenities and farming. CLTs are set up and run by ordinary people to develop and manage homes as well as other assets. CLTs act as long-term stewards of housing, ensuring that it remains genuinely affordable, based on what people actually earn in their area, not just for now but for every future occupier. [i] From 2003-2009, we worked as a member of a CLT National Demonstration Project with the New Economics Foundation, a university, housing bodies and the government to develop templates, funding and pilots such as Stroud’s Cashes Green CLT, designed by Kevin McLeod of Grand Designs. There is now a national enabling body and over 290 CLTs, with government support for community led housing. For those interested in Jersey, Cornwall offers many successful examples of village and town CLTS, such as the St Minver self-build scheme, enabled by Cornwall Rural Housing Association.[ii]

Rock in North Cornwall is in an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, is a desirable holiday destination, and a second-home hotspot. St Minver CLT has to date provided 20 self-build homes in the parish.

We were also interested in local food, so we helped to start Stroud Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) as an exemplar. This is now a charitable co-op of 375 members, 3 farmers with sales of biodynamic vegetables and meat totalling £185,000 p.a. Some villages around Stroud are now considering starting their own CSAs for tackling food security and food poverty.

One big issue was land access for CSAs, so between 2004 and 2007 Stroud Common Wealth got funded to enable community buy outs of farmland for affordable access for farmers and communities. Our first project was Fordhall Farm, where the owners were selling the farm from under the feet of the third-generation organic family farmers. We facilitated the community buy out of the farm, forming a charitable community benefit society co-op that raised £800,000 from over 8000 members in using what was then a little-known method of investing in community shares. Ben and Charlotte Hollins, the farmers, have created over 25 jobs on a 123-acre farm that only had one job, and a cluster of thriving food businesses, educational and environmental activities.

Such local projects are all very well, but if successive governments deliberately encourage ever higher house and land prices for political gain, then we are merely ‘pushing a river’. For example, the UK Treasury wanted a full price for the Cashes Green land for the CLT, which meant much less social housing.

So secondly, what is the cause of ever higher land prices? And what is the alternative of ‘land as a commons’, of ‘land’ as a bundle of rights? The ever-higher housing prices result from treating land as a commodity, to be bought and sold on the market rather than as a shared commons over which we have a bundle of rights. These include mineral, access, building, farming, fishing, hunting, wooding and other rights. For example, in Stroud, we have an example of ancient commons governance. The freeholder of Rodborough and Minchinhampton Commons is the National Trust, with a commons association that regulates ancient grazing rights, rights of way, access, golf and wildlife areas. Such commons are a leftover from pre-feudal, pre-enclosure days; such commons governance is widespread.

Think of local fishermen regulating their traditional fisheries, or centuries old common pasture management by farmers in the Swiss Alps. The Isle of Man created a new commons when thousands of people cleared their beaches of rubbish. Their aim of protecting the coastal waters from the multiple threats of plastic pollution, climate change and overfishing earned the Isle of Man the status of an UNESCO Biosphere region, uniquely designated because it is an outstanding example of a place where people and nature work in harmony. The state created the legal framework, but people develop and maintain their own rules, such as for inshore fishing. Community Land Trusts offer governance for stewarding land as a commons for individual benefit and the common good.

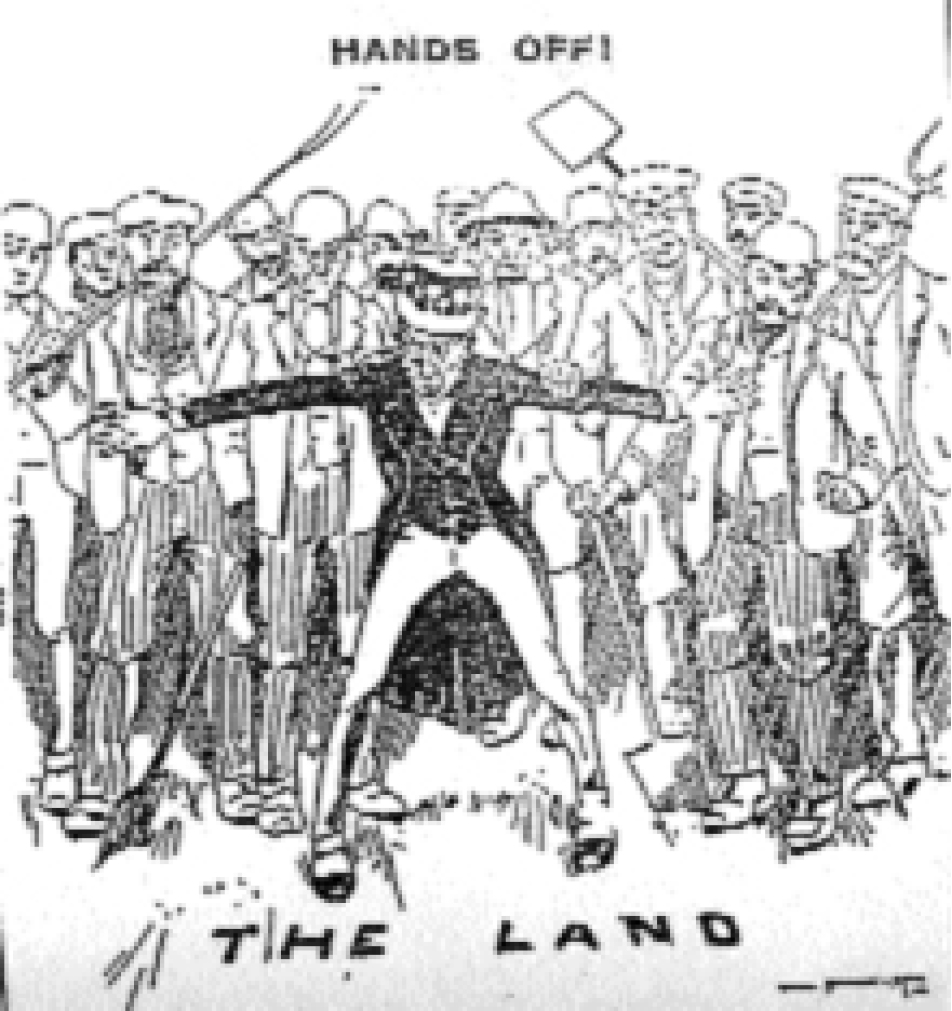

Starting in Tudor times, as soon as our commons were enclosed, land became a commodity to be bought and sold on the market. Winston Churchill argued in Land for People in 1909, that land is by far the greatest of monopolies and therefore needed controlling. The owner of an empty house or derelict plot of land has only to sit still and watch his property multiplying in value, without either effort or contribution on his part. He argued unsuccessfully for a Land Registry so that everyone in Britain could easily find out who owned what land and a land value uplift tax, but brought in death duties on landed estates.

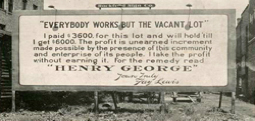

Henry George asked, ‘Why was there so much poverty amidst so much progress?’

Here is a billboard illustrating the unearned profits just from land ownership

Churchill would have approved of a June 2019 report called Land for the Many: Changing the way our fundamental asset is used. [i]This aims to put land where it belongs, at the heart of political debate and discussion. It proposes radical but practical changes in the way land in the UK is used and governed. It reflects on how land ownership and control in the UK has led to soaring inequality and exclusion, high rentals and no hope of home ownership for many young people, the collapse of wildlife and ecosystems, repeated financial crises, and the loss of public space. Here are some stunning facts from the report:

* Since 1995 land has increased in value from £1tr. to £5 trillion;

* By 2016, the cost of land accounted, on average, for 70% of the price of a home;

* The price of agricultural land increased 462% since 1995. Stroud Common Wealth is using the report’s useful analysis and policy recommendations to engage with civil society, local government and business to tackle urgent questions. These include: ’How do we build truly affordable social housing? How do we support communities to provide their own homes? How do we reclaim and re-purpose empty properties? How do we respond to the homelessness crisis? Perhaps most importantly: how do we protect nature and all the benefits it provides us, including food, health and wellbeing, protection from flooding and protection from the worst impacts of climate breakdown?

How can we reclaim and re-purpose Tricorn House, Stroud? An eyesore, empty for over 20 years, owned offshore: A Compulsory Sale Order?Ownership transparency? Tax this empty property? [i]

If Jersey people are interested in reviewing the extent to which its land system is working for the common good, then Land for the Many is thought provoking, though of course Jersey has a unique land story. The report recommends improving Britain’s land ownership system by rebalancing the public, private and community, civil society sectors through:

* Publishing all information about land ownership, control, subsidies and planning as open data, including the identities of beneficial owners to increase transparency;.

* Introducing a Community Right to Buy based on the Scottish model, in the other three nations of the United Kingdom;

* Introducing Compulsory Sale Orders, which would grant public authorities the power to require land that has been left vacant or derelict for a defined period to be sold by public auction;

* Introducing an Offshore Company Property Tax payable by companies based, or beneficially owned, offshore which own land in the UK.

On urban planning the report recommends:

* Reforming the Land Compensation Act to enable public authorities to acquire land at prices closer to its current use value, rather than its potential future residential value;

* Stopping the sell-off of public land to the highest bidder and using public land to deliver affordable housing and other social needs;

* Democratic participation in planning by introducing a form of jury service for plan-making.

On rural land the report recommends:

* Widening access to farming, by halting and reversing the sell-off of County Farms and creating opportunities for small farmers;

* Extending the planning system to cover major farming and forestry decisions;

*Adopting the Scottish principle of a Right to Roam across all uncultivated land and water, excluding gardens and other exceptions.

These recommendations are all very well as springboards for thinking, but have the disadvantage of NIJ (Not Invented in Jersey. So lastly, how can Jersey engage with improving how land as its fundamental asset can be used, owned and governed? Powerful drivers for this land review include: how to adapt to global warming and the climate emergency; how to improve food security and tackle food poverty; how Jersey might feed; how to bring down the price of housing, tackle inequality and help young families; how to enable young entrant farmers with land access; how to protect Jersey’s commons such as its biosphere. Farmers, communities and businesses may well act in their own backyards. However, just as Stroud developed its community plan, Jersey could engage the three legs of civil society, business and government in a search conference. The purpose could be to develop the most desirable future for the land system in Jersey, and how to realise this. And there are many good Jersey stories to learn from and build on.

[1] See Large, Martin, Common Wealth, Hawthorn Press, Stroud, UK 2010, Large, Martin, and Briault, Steve, Free, Equal and Mutual: Rebalancing Society for the Common Good, Hawthorn Press, Stroud (2018); Conaty, Pat, and Large Martin, editors, Commons Sense: Co-operative place making for 20th Century Garden Cities, Co-operatives UK, Manchester, 2013

[1] www.communitylandtrusts.org.uk/

[1] Land for the Many Report can be viewed in full here: www.labour.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/12081_19-Land-for-the-Many.pdf

Authors include: George Monbiot (editor), Robin Grey, Tom Kenny, Laurie Macfarlane, Anna Powell-Smith, Guy Shrubsole, Beth Stratford.

[1] Tricorn House see: blog.shelter.org.uk/2017/07/the-tricorn-house-mystery-shelter-investigates/