By Dr Paul Chambers, Jersey Heritage’s Head of Geopark

In the spring of 1890 a young man from England stepped onto the St Helier quayside carrying a suitcase full of glass jars, metal sieves and scalpels. This was James Hornell, a graduate of Liverpool University College who had come to Jersey in search of marine specimens from the island’s legendary rocky beaches and seagrass beds. Within weeks Hornell had fallen in love with Charlotte, the daughter of a well-known local naturalist named Joseph Sinel. The pair were married and Hornell moved to the island.

Sinel and Hornell shared a passion for marine biology which led their founding The Jersey Aquarium at Havre des Pas which was part tourist attraction and part scientific laboratory. Initially the Aquarium did well, receiving upwards of 300 visitors a day but Sinel quickly lost interest, leaving his increasingly irate son-in-law to do the donkey work. Hornell complained that he could only make the Aquarium work ‘by stealing the necessary time from hours which by right should be devoted to relaxation.’ The work was too much and the Aquarium closed its doors, triggering a feud between Hornell and Sinel became something of a public spectacle.

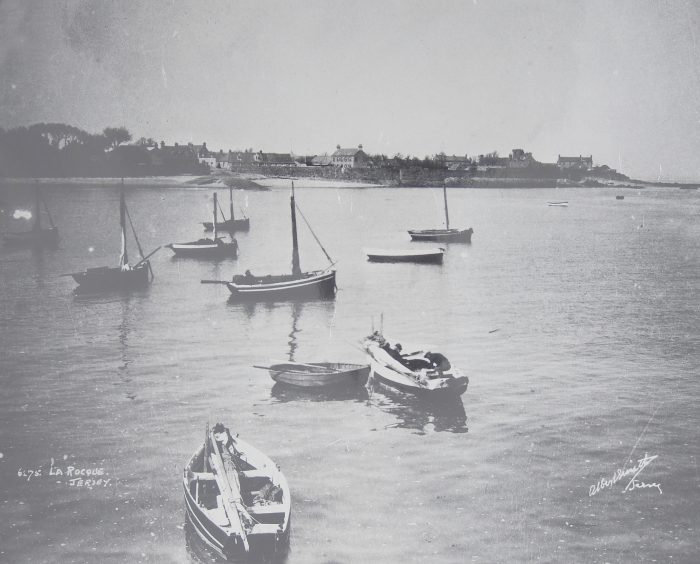

When it came to seafood, Jersey had historically been self-sufficient but by the mid-1890s the island had become reliant on imported mackerel, flatfish and even oysters which had at one time caught in their millions. This didn’t surprise Hornell as he had studied fisheries science in Liverpool and, on first arriving in Jersey, had been ‘astonished at the scarcity of fish, the quantity that is taken being ridiculously small.’

At this time Jersey was one of the few British places to any fisheries laws, as most UK fishing regulations had been swept away in 1868. Even so, the Jersey laws were minimal and had not kept pace with the advent of new fishing techniques such as the use of poisons and dynamite. In the absence of official statistics, Hornell had collected his own figures and in 1897 delivered a public lecture which detailed a decline in key stocks such as lobsters, crabs and flatfish. This he blamed on a combination of overfishing and lack of regulation.

Local opinion was divided until a severe shortage of ormers and flatfish led to a public petition for better management. Hornell was consulted and in 1901 the States voted through a Fisheries Regulation Bill which introduced minimum fish sizes, restrictions on inshore trawling, closed seasons for certain species and salaried fisheries inspectors. Newspapers noted that ‘the fishermen themselves are divided in their opinion as to the utility of the regulations as a whole, and the coastal parishes are hardly unanimous in any single particular.’

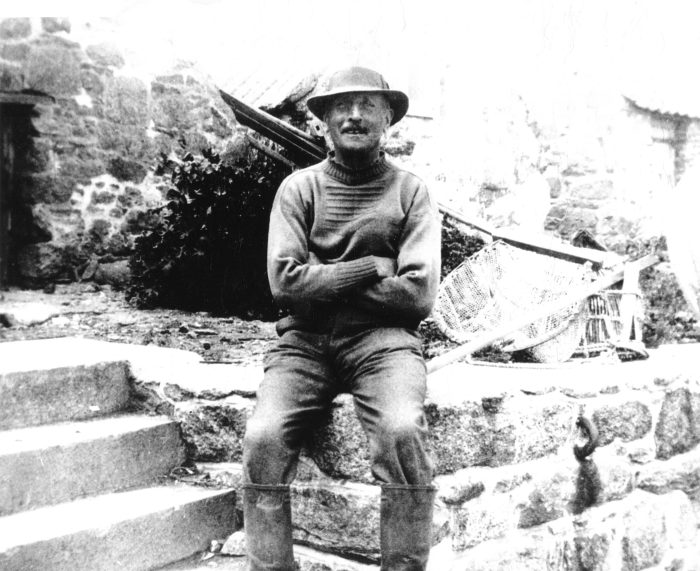

The new regulations gave Jersey the world’s most highly regulated fishery but Joseph Sinel was not at all happy. He was a follower of the scientist Thomas Huxley who had famously declared that fishing, no matter how intense, would never impact stocks. ‘If [the Law] is intended to protect the fish numerically,’ wrote Sinel, ‘it is ridiculous … if all now on this shore were basketed it would not decrease the ever renewable supply.’

Sinel began campaigning against the new regulations and also against his son-in-law, whom he viewed to be an overeducated outsider. The pair exchanged many bitter words through letters to the newspapers and via public lectures. Sinel wanted the States to ‘stop this practical imbecility’ while Hornell warned that without regulation he could not ‘see any real hope for our fisheries’.

The clash of views was quickly dubbed ‘Sinel vs Hornell’, with journalists taking delight at reporting the rancour between former allies. After 18 months it was Hornell who capitulated by accepting a job as Inspector of Fisheries for Sri Lanka. In 1902 he left Jersey permanently and eventually became a global authority on fisheries management and, bizarrely, the design of ethnic dugout canoes.

Sinel stepped up his opposition, claiming that local people, and not interfering scientists, were best placed to judge the viability of Jersey’s fishing stocks. ‘Our Fishery Law which I have so often attacked with tooth and claw,’ wrote Sinel, ‘rests upon a total lack of natural history knowledge.’

In 1907 Sinel organised a petition to the States of Jersey requesting the removal of all local fishing regulations. ‘It appears trawling is what the fishermen want most,’ reported States’ member Edward Renouf to the Assembly. ‘They are most anxious to come within the [closed] limits to trawl where fish can be found. The fishermen wish to take the immature fish which prevail within the limits.’

The law was duly amended to remove a majority of the 1901 fishing regulations and, for good measure, to legalise the shooting of cormorants as they ‘eat their own weight in fish a day.’ The lack of fisheries management aligned Jersey with the UK and produced a short-lived boom as trawlers entered bays that had been closed to them for several years. For a brief while local newspapers carried articles about large catches of fish which they ascribed to ‘the withdrawal of a prohibition for which the fishermen of the island should be grateful.’

The success was short-lived and within five years there were renewed complaints about small catches and a shortage of fish. By the start of World War One a majority of the island’s seafood was again being imported from the UK and France. By then Sinel’s interests had moved away from fish to more esoteric things such as clairvoyance and ghosts.

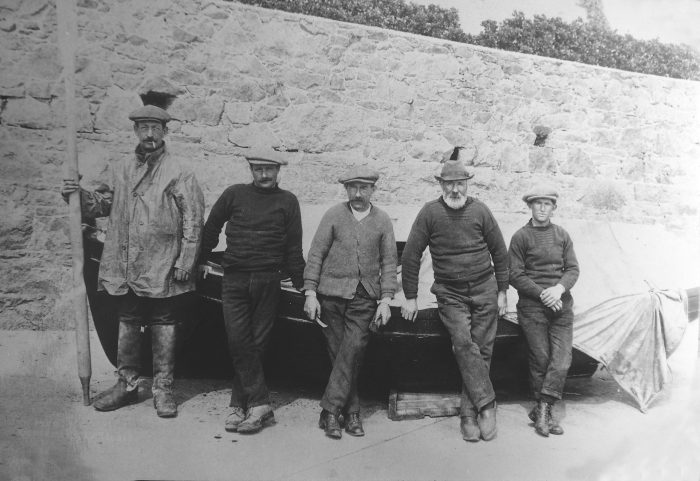

When Hornell arrived in Jersey in 1890 there had been 177 full time fishers which, by the 1901 law’s enactment, had shrunk to 154. The post-1907 boom saw the numbers rise to 194 but by 1930 a lack of fish saw the industry down to 90 people. A scarcity of flatfish meant almost all fishing was for lobster and crab, a situation that still persists. By 1940 the commercial industry was down to a handful of boats. ‘It is,’ remarked an ageing La Rocque fisher, ‘a great sorrow not to be able to fish the islands as we and our fathers have always done. At the present time it is impossible for us to do so.’