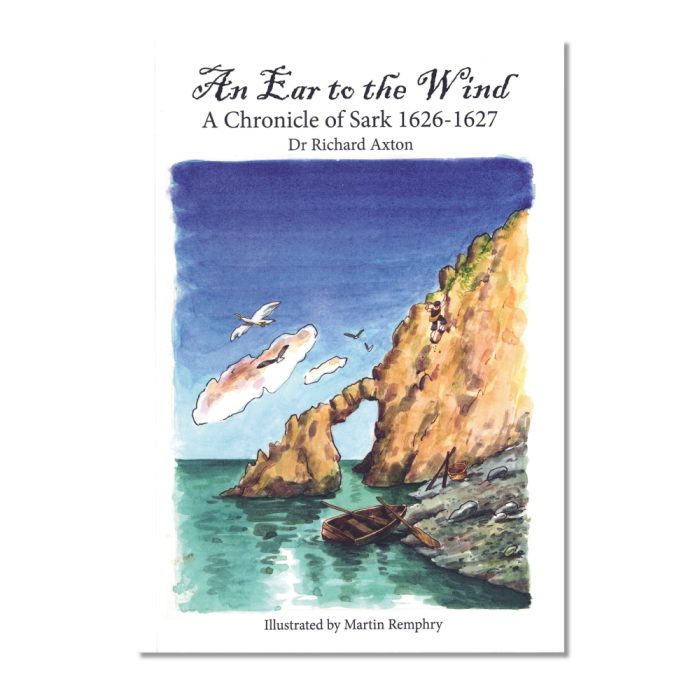

Book Review by Alasdair Crosby

A Chronicle of Sark 1626-1627

By Dr Richard Axton

I have just returned from Sark – well, metaphorically speaking. It was not today’s Sark, but the Island of Sark in the 17th Century. My knowledgable guide has been Dr Richard Axton MBE, an eminent scholar, Emeritus Fellow of Christ’s College, Cambridge, a great lover of Sark and latterly a resident there; in his later years Richard led the Société Sercquaise as director and archivist. He received the MBE in 2021 for his services to heritage and the environment in Sark.

To my great regret I never met Dr Axton; we corresponded about the re-establishment of an Island dairy in Sark – another of his many interests – and I was due to visit the Island. Then the pandemic of 2020 intervened, and that was that – the visit never happened. He would have been an excellent guide to the Island of today – but unfortunately, he died in November 2021; his present book has been published posthumously by his daughter, Lucy.

At least I have had the good fortune to read his chronicle of Sark for 1626-1627, the result of his scrupulous research among court records and the diary notebooks of the Calvinist Minister on Sark at that time.

The famous archaeologist, Sir Barry Cunliffe, describes the book as ‘historical research at its very best’ and proves the point that what many would see as dry as dust research among boring old archives can actually provide information of extraordinary interest and immediacy.

In the case of Dr Axton’s book, this research is a guide to daily life in Sark for its inhabitants of the time – a generation that included grandchildren of the original settlement of Sark in 1565 by the Seigneur of St Ouen, Sir Helier de Carteret; in the 1620s it was still part of the seigneurial fief, but was becoming more of a dependency of Guernsey, with more serious crimes on Sark being referred to Guernsey’s Royal Court.

And what was daily life like in Sark? Very rural, of course, with all the advantages and disadvantages of life in a small community, as well as being hard and with a lack of personal discrimination for Islanders in the way they chose to live their lives. This was due to the rigid nature of the Calvinist culture and of the leading hommes de bien, who took a dim view of merriment, dancing, playing music and even calling people names – they were all matters of crime and punishment. Collecting samphire from the cliffs was one way of making a small income for oneself, but scrabbling on precipitous slopes could lead to a fall and death on the rocks below. And venturing on to the seas in the small fishing boats available often caused death by drowning: such cases would have a serious impact on a small population.

There was some witchcraft – and that could lead to prosecution in Guernsey’s Royal Court if found guilty, death by hanging. Then there was the scandalous case of incest by the Island’s miller with his daughter. He was an unpopular man in the Island, so there was no grief when the Guernsey Court found him guilty, had him whipped around the town and cut off an ear as punishment.

So, the book could be described as an everyday story of Island folk, with the descriptions of drama, life and death. Like a 17th Century ‘The Archers’, but a soap opera far more compelling and interesting.

The text is complemented by drawing by the Sark artist, Martin Remphry. Both the Société Jersiaise and Jersey Heritage have copies of the book on sale (£15). It can also be ordered from lucyemaxton@gmail.com