Rural – Jersey Country Life Magazine

What’s for Dinner?

Introduction

The Macro Themes

Farming – What Sort?

Something To Eat

Food and Farming in Jersey – New Models

The Natural Environment

Postscript to ‘What’s for Dinner?’

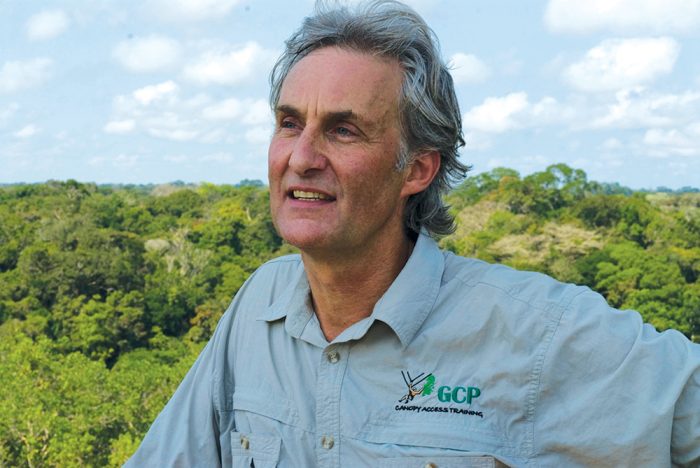

A Lifetime Fighting For Forests

By Andrew Mitchell

I started out in Jersey learning the language of chickens. This art form has stood me in good stead throughout my life whilst engaging scientists, politicians, CEOs, bankers and strange tribes deep in the rainforest. They all have different languages, especially where protecting the environment is concerned.

At the age of six, crouched in a barn surrounded by 50 Sussex whites, I soon learned the hen’s complex signals indicating attract or repel, food or flight, contentment, and resentment that permeated the flock, which to others was just a group of stupidly clucking chickens. Such skills have proved invaluable whilst chairing meetings of competing Governments on climate change, bemused bankers on biodiversity and even the Swinbrook Parish Council!

My life growing up on a Jersey farm in Grouville, immersed in love and a sense of adventure, was peppered with stories of a grandmother’s unfortunate adventures in Argentina, a grandfather’s search for the ‘lost City of Z’ in the Amazon and other relations settling in the dubious parts of New Zealand. Fortunately, the ‘Z’ adventure was declined by my forbear, so I am here, but its leader, Colonel Percy Fawcett, vanished forever into the rainforests of the Xingu.

‘JBS’

Armed with a degree in zoology, coupled with a splash of philosophy, I was well equipped to engage my thirst for rainforest adventures. I fell under the spell of Gerald Durrell books, his orangutans in the Zoo and later met an extraordinary mentor, 40 feet underground in the Ministry of Defence in London, also a Jerseyman. It seems there is a kind of global Jersey ‘Mafia’ in the business of exploring and saving nature.

Back then, in 1977, I faced this very large Victorian looking gentleman, clothed in green fatigues, sporting a pencil thin black moustache topped by a solar topee. ‘On to Panama!’ he shrieked, and so off we went, for what he described as the office party – it was in fact an expedition into the impenetrable Darien jungle.

Room 5B in the Old War Office Building became revered as the lair in which Col. John Blashford-Snell’s great expeditions were formed, under the enthusiastic but occasionally nervous patronage of Prince Charles. JBS as he was known to all, was indeed an ‘Old Victorian’, (as are called Old Boys of Jersey’s own public school, ‘Victoria College’), but he was destined to straddle the globe, leading some of the largest expedition’s ever to leave the UK. I became the Scientific Co-ordinator of the Scientific Exploration Society, an institutional home for his exploits, and had the good fortune to help plan the field programmes of Operation Drake and later Operation Raleigh in the early ‘80s.

For a graduate looking like Che Guevarra, with the same desire for adventure but without the benefit of a gun, these challenging enterprises brought me into the frontline of conservation in Panama, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia and Africa, and many islands in between – and changed me forever. JBS’s legacy is that over 40,000 young people have now benefitted from these challenging expeditions, sustained by what today is known as Raleigh International. Together we invented ‘the Gap Year’.

Whether tracking wildebeest on the African plains, or hanging from ropes in the rainforest canopy, or diving on coral reefs searching for wrecks, there is nothing quite as exciting as coming face to face with nature in the raw. It’s power, yet vulnerability has never ceased to amaze me. A one thousand year old giant redwood can be felled within minutes by a chain saw. A charging rhino that will flatten a land rover can be stopped by a poacher’s bullet. Tossed back into the sea, its fin removed, a shark becomes a pathetic imposter, slowly sinking into the deep. Seeing this happening all over the world during my lifetime, has created a sense of seething anger and butterflies beneath my otherwise optimistic exterior.

Decades of destruction

In the 1980s I briefly joined the late Adrian Cowell, making a film series called Decades of Destruction for Central Television. It was the first to open the eyes of the world to the landscape-scale conflagration emerging unseen in the Amazon. I had spent the previous years pioneering the construction of aerial walkways in the rainforest canopy, built not by me, but the brilliant Royal Engineers under JBS’s command. This too had opened up my mind the where ‘life meets the atmosphere’ and the incredible un-quantified power of rainforests to keep our atmosphere cool and our landscapes filled with water for crops. Its magnificent biodiversity of bees, butterflies and birds, are simply the workers in a giant tree based eco-utility that keeps our earth safe. All the more devastating to see it vast areas of it, on our editing screens in north London, going up in smoke.

After a spell at the BBC Science and Features and Natural History Units, I left concluding that being in front of the camera was more rewarding than being behind it. I was even deluded enough to think that I might be a good follow-on to Sir David Attenborough. I had not bargained on him living for almost a century and still going strong! A young journalist asked me at this fork in the road, what do you want to be? I answered ‘An Ambassador for the Planet’. Seemed like a good idea at the time.

I first met the ‘Trinity girl’ (Jersey people have traditionally been known by their home parish in the Island – in my wife’s case, the Parish of Trinity) who would later become my wife, when I gate-crashed her 21stth birthday party, fortunately disguised as a punk rocker. Venues in St Helier were not used to this look, and I – along with a number of other guests in similar attire – were ejected – but a fire was kindled. A decade later we met again on the set of the Warner Brothers movie, Greystoke – the Legend of Tarzan. I was the rainforest adviser and she, on behalf of the producers, penned my P45. She said the directors were getting too excited about my ideas for exotic rainforest locations. On returning from extended leave whilst journeying across the South Pacific to Easter Island, it was a case of third time lucky and Laura and I married at Trinity Church in 2008. She has proved the eternal family rock while I continued to fight for forests.

I discovered Easter Island has no trees. But once it had forests of huge Jubea palms. These were all felled by humans, eager to roll statues from one side of the island to another in the name of – well what? Ego? Perhaps. But certainly some kind of worship.

I wonder if our love of giant towers in cities is a similar kind of worship – to the ‘model of More’. It is intriguing that the very largest statues ever built on Easter Island, were the ones never erected. War broke out. It was as though, to take their minds off the impending doom of a destroyed natural ecosystem, the sages of the time distracted the workers with ever greater feats of folly – all in the name of more of the same.

Natural capital

After launching Earthwatch Institute in Oxford, and 12 years later Global Canopy, a think tank, also in Oxford, I found I needed the help of a much bigger voice, if destruction to the world’ s ‘Natural Capital’ was to be turned around. I found this in the form of HRH The Prince of Wales. The result of our collaboration was the creation of his The Prince’s Rainforests Project. Within months he had cleared a top floor in Clarence House and crammed 20+ highly intelligent enthusiasts into it. Our aim was to create a sense of emergency and to persuade Governments that “Rainforests are worth more alive, than dead”. Prince Charles’ use of that phrase, was, much to my satisfaction, repeatedly echoed around the world, especially by Ministers. His Emergency Plan for Rainforests catalysed US$ 4.5 billion being allocated from Governments in 2008, to help confront deforestation worldwide. It was the largest amount for rainforest conservation ever – but it has not proved enough.

The reason is simple. While governments were busy spending around one billion US dollars a year to stop deforestation, the private sector was financing activities that were destroying them, of about150 billion US Dollars annually. 70% of rainforest destruction is caused by clearing land for the production of agricultural commodities used worldwide. Soya feeds Jersey cattle and Chinese pigs and chickens. Much of it originates from land once covered in Brazilian forests in the Amazon or the Cerrado. Beef ranching has been the primary cause of land conversion in the Amazon, over the last 30 years. Brazil is the world’s biggest exporter of beef and leather products. Palm oil in SE Asia is imported into India, Europe and China as a cooking oil, food additive, or smoother of ice creams. In the EU almost half the imported palm oil ends up in petrol tanks as a biofuel, to reduce emissions from European vehicles.

Folly

The folly is that burning trees for land, drives almost the same amount of emissions into the atmosphere, as all the world’s cars, ships and planes put together. In 2015, 135,000 Indonesians were admitted to hospital with respiratory problems, in part driven by our demand for palm oil. Airports, as far away as Singapore, were closed by the resulting smog. In the last two decades some scientists estimate 150,000 orangutans have died because of clearance of their habitat.

Combatting deforestation and delivering low carbon agriculture offers 37% of what we need to do globally to stay below a 2 degree temperature rise, driven by rising CO₂ emissions. Yet such ‘Natural Climate Solutions’ get just 3% of the global finance to combat climate change. Most goes on energy, infrastructure and transport projects. Why is it so difficult for the penny to drop?

Perhaps it is a bit like betting on the horses at Jersey’s Les Landes Racecourse on a Bank Holiday Monday. You read the form, listen to what the experts are saying and then bet on the favourite. For some reason with climate change, many of us do the exact opposite and despite all the evidence, prefer to bet on the 100:1 outsider. Like turkeys abstaining on a vote for Christmas, we don’t want to believe that ‘really bad shit’ is going to happen!

About 20 years ago I realised that hugging orang-utans was no way to save them. So I left the rainforest canopy and began to climb about in business boardrooms. I poked my nose into the data they use to make financial decisions. I had to learn a whole new language. They didn’t understand any of mine. I discovered something weird. Impacts on nature and forests were mostly invisible on their balance sheets. The only metric that mattered was financial capital (‘profits’ to you and me). I looked inside the data terminals that inform 70% of financial decision making on the planet, and I found them empty of data on natural capital. It was like walking into an Aladdin’s Cave of critical information, and finding that half of it was missing.

Investing blind

I was horrified. This was why an investment in a palm oil company looks so good, because the cost of destroying the rainforest and killing 150,000 orangutans, appears nowhere in the share price. That meant the biggest pools of capital deployed on the planet were investing blind as to their impacts on nature. Little wonder we are loosing the battle.

After six months of bellyaching I got in front of the Chief Investment Officer of my pension fund, responsible for some US$99 billion of client funds under management and asked him if my pension was destroying rainforests. He said no one had asked him that before and that he had no means of knowing and no legislation existed, that required him to know. So that was it! No tools to know existed, and there were no incentives to use them, even if they did. Here was David’s sling and a possible stone with which to wake up the Goliaths of finance to the risks into which they were sleepwalking. But how could I shake them out of their complacency?

In 2012, I launched the Natural Capital Finance Alliance (NCFA) to do just that, but it was always going to be an uphill battle. Fortunately, the Bank of England and the Extinction Rebellion have recently come to my aid by creating the conditions for a revolution in our economy. I cannot remember a time when the Governor of the Bank of England and activists in the streets have ever called for the same thing. Action on climate change! Mark Carney has said that organisations that fail to adapt to these new conditions, will simply go extinct. Now that’s my kind of language! It is increasingly clear to me that unless we re-incentivise the movement of money, we will continue to finance ourselves into extinction.

The current plan in my fight for forests was inspired by the architecture of a Guernsey chancre that I happened to enjoy eating in Port Baille. In one crab claw, experts would design the tools that can enable finance to understand their impacts and dependencies on nature, and in the other, the larger one, Governments would deliver the regulatory pinch that forces banks, investors and insurers to be more transparent and risk sensitive, by using the tools.

In January 2019, I began advocating for a financial sector reporting Framework for Nature – the more powerful of my two crab claws. NCFA has already released the ENCORE – a tool that for the first time allows financial institutions to screen their portfolios for dependencies on nature. I am amazed to sense the momentum for this approach currently building around the world. In June 2019, the UK Government announced that a task force for Nature Related Financial Disclosure is now part of official policy under the UK’s new Green Finance Strategy. In October 2020, China hosts a ‘Nature Summit’ where I hope what is called the Global Deal for Nature might be struck – committing Governments to protect 30% of the earth’s surface by 2030 and 50% by 2050.

It is not a bold dream: it is Earth’s survival plan.

Fighting for forests is a David and Goliath situation.