Marie-Louise Backhurst considers corn, mortgages and riots in Jersey’s history; from RURAL’S archives – first published in 2013

In the last forty years or so, Islanders may have become accustomed to seeing potatoes or other vegetables growing in Jersey’s fields. Rarely are any cereals seen. Yet bread is a staple part of the human diet; the demise of the largest bakery in Jersey due to production high costs is not perhaps wholly unexpected.

Yet growing cereals and wheat – in particular – have been a part of Island life for centuries. Archaeological investigations show that pre-historic cereal pollen found in some sites dates back about 6,000 years ago. This would suggest that Neolithic people had settled in Jersey and were cultivating land.

Wheat became an intrinsic part of life in Jersey, not just for its food value, but because it was used as currency. The price of wheat was fixed annually by the Royal Court and payments (rentes) for leases or charges on land and houses were frequently made in wheat. This necessitated careful weighing which was also overseen by the Royal Court and granite stones for weighing became commonplace. The weights usually represent fractions of the Jersey hundredweight (known as a quintal). Thus they may weigh 104lbs (a quintal), 52lbs, 26lbs or 13lbs etc, but other weights were used. The weight is usually inscribed on the stone which were usually made from pebbles from the sea shore.

After the loss of Normandy by King John in 1204, the Island was frequently attacked by the French; one raid, about 1294, reported that 1,500 inhabitants (about 10% of the population) were killed and the mills and corn were burnt, leaving the survivors with nothing to eat.

Jersey’s earth has long had a reputation for high levels of fertility; combining that with a temperate climate and adequate rainfall meant that at some times more wheat was grown than was needed for the local population. In 1523 there is a record of wheat being exported from St Aubin to Spain.

A corn market (L’Halle à Blé) was built in St Helier in 1583 with money raised from all the parishes; it was opposite the church on the site which was, until recently, the Midland/HSBC bank building. Nearly a hundred years later in 1668 a new corn market was built – which is not the United Club but the Superintendent Registrar’s Office, where the original massive granite pillars can still be seen.

Writing in 1686 the then Bailiff of Jersey, Jean Poingdestre, spoke of half the corn needed in the island having to be imported. The introduction of cider apples led him to remarking: ‘the whole island is in danger of becoming a continual orchard.’

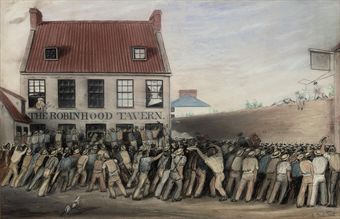

There was a dearth of corn in 1767 and its export was banned; this was repealed the next year following a good harvest. However there were advantages to exporting corn because it kept the price of the wheat rentes high which benefited those who had loaned money. This led to a raid by a mob of women on a ship in the harbour which was full of corn ready for export. On 28 September 1769 matters came to a head with a large group of about 2,000 men marching from the country parishes to the Royal Court demanding, amongst other things, a reduction in the price of wheat. Far-reaching reforms that came into effect as a result were codified in 1771.

The rising costs of bread provoked a riot again in 1847 that saw an angry crowd gathering near the Town Mills in Grands Vaux. As a result of the demonstration the States had to subsidise the price of bread for the poor.

The type of wheat most commonly grown was known as Tremais –meaning that it took three months from sowing to harvest. Recently a trial of this wheat was made at the Howard Davis Agricultural Centre.

Cheap bread may become more readily available, but it cannot match the variety of home-baked bread, which can be just as inexpensive.

If you would like to try making your own bread, why not use flour which has been milled at Quétivel Mill? The National Trust for Jersey sells stone-ground whole-wheat flour from their headquarters at The Elms, St Mary.