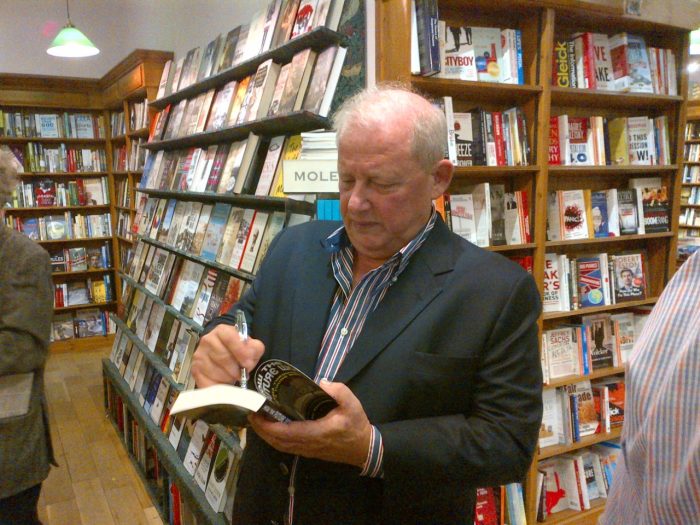

By our guest contributor, Alexander Boot, a Russian-born writer of books and articles, previously a university lecturer and an advertising and public relations executive. His work promotes traditionalist conservatism and European culture. See further: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Boot

He visits Jersey regularly to visit relations. Actually, Marx was also a visitor to Jersey between the 1850s and the 1880s, together with his friend, Friedrich Engels. They were not too complimentary about Jersey; Alexander is not too complimentary about Marx

Last week was the 141st anniversary of Marx’s death, an event worthy of joyous festivities. God only knows how much more harm he would have caused had he lived beyond age 64.

Since for 70-odd years the most formidable propaganda machine in history was dedicated to spreading Marxism, many feel they know what Marx is all about without having to resort to the primary source. That’s a pity, for if more people had actually read the Communist Manifesto, one hopes there would be fewer innocents insisting that Marx’s ideals were wonderful but regrettably unachievable; or else that Marx’s theory was perverted by Soviet practice.

In fact, Marx’s ideals are unachievable precisely because they are so monstrous that even the Bolsheviks never quite managed to realise them fully, and not for any lack of trying.

For example, the Manifesto prescribes the nationalisation of all private property without exception. Even Stalin’s Russia in the thirties fell short of that ideal. In fact, some 15 per cent of the Soviet economy was then in private hands.

Marx also insisted that family should be abolished, with women becoming communal property. Again, for all their efforts, Lenin and Stalin never quite managed to achieve this ideal either, much to the regret of those who could see an amorous pay-off in such an arrangement.

Then, according to the Manifesto, children were to be taken away from their parents, pooled together and raised by the state as its wards. That too remained a dream for the Bolsheviks who tried to make it a reality, but ultimately failed.

Modern slave labour, such an endearing feature of Soviet Russia, also derives from Marx – and again Lenin and Stalin displayed a great deal of weak-kneed liberalism in bringing his ideas to fruition.

Marx, after all, wrote about total militarisation of labour achieved by organising it into “labour armies”. Yet no more than 10 per cent of Soviet citizens were ever in enforced labour at the same time.

The only aspect of Bolshevism that came close to fulfilling the Marxist dream was what Engels described as “specially guarded places” to contain aristocrats, intelligentsia, clergy, etc. Such places have since acquired a different name, but in essence they are exactly what Marx envisaged.

Here Lenin and Stalin did come close to fulfilling the Marxist prescription, but they were again found wanting in spreading concentration camps to a mere half of the world. So where the Bolsheviks perverted Marxism, they generally did so in the direction of softening it.

All such monstrous practical prescriptions of Marxism lie on the surface, for anyone with eyes to see. None of it, however, explains the influence of Marxist philosophy even in countries described as liberal democracies. One thing for certain: for a philosophy to gain such a lasting influence, it has to inhale the zeitgeist and then exhale it with a tsunami force.

That’s what Marxism did, thereby answering the need keenly felt by post-Enlightenment mankind. The Enlightenment, that great misnomer, was essentially a mass rebellion against Christianity, which was seen as superfluous to the needs of nascent modernity.

That, however, left a philosophical vacuum that had to be filled. Man, after all, is a reasoning creature, and he needs to make the world intelligible. Christianity achieved that end by providing a coherent explanation of life, man and nature that vindicated its founding faith. Now the founding faith was lost, a materialist surrogate was urgently needed.

However, when a religion goes, it’s never replaced by naked materialism. It’s invariably replaced by a determinist cult absolving people of individual responsibility for their salvation and treating history as a sequence of predetermined tectonic shifts, with people at their mercy.

The elements of such a cult were already in place by the time Marx came about. He himself cited as his three major sources Hegel’s dialectics, Smith’s economics, and the utopian socialism of Campanella, Fourier and Saint-Simon.

Hegel equipped Marx with the dialectical method, but Adam Smith did so much more than that. His philosophy posed as sheer rationalism, but was in fact pure metaphysics with a sorcery dimension.

According to Smith’s moral philosophy, each individual must pursue nothing but his own interests, mainly economic. One could get the impression that this would create a society of atomised, amoral individuals, but that impression was wrong, explained Smith. All those private interests would be tossed into a giant pot, where they would be stirred by an invisible hand in such a way that the resulting stew would emerge homogeneous and moral.

That was the beginning of what I call totalitarian economism, allowing economics to claim the universality formerly reserved for religion, theology and priesthood. Thus Smith indeed exerted a formative influence on Marx, but not only on him.

Not just Marx but also Hayek, Mises, Friedmann and other ‘conservative’ economists applied Smith’s ideas to modern needs. As a result, modern man divided into two streams, which I call nihilists and philistines. Both carry Marx’s genes in their DNA, but siblings can be similar without being identical.

Marx interpreted Smith’s invisible hand as class struggle, with people forced to act in a certain way by their demographics, something Marx called “relationship to the means of production”. Since the have-nots are more numerous than the haves, they are slated to emerge victorious in the long run. The long run could be made shorter by physically eliminating the classes putting the brakes on predestined progress.

Hayek et al. ignored the cannibalistic strain of Marxism, but they too tried to fill the void left by Christianity with economic superstitions. If Marx believed that mankind was divided into hostile classes to begin with, only then to arrive in due course at a uniform bliss he called “dictatorship of the proletariat”, Hayek’s society started out as a conglomerate of selfish individuals who were then guided by the invisible hand to collective morality.

Totalitarian economism with a superstitious dimension is evident in both strains, which makes them dislike each other: none so hostile as divergent exponents of the same creed. Yet anti-Marxism is but Marxism with the opposite sign, which is why, much as the two groups proclaim mutual hatred, they continue to survive side by side in our liberal democracies.

Both testify to the barren philosophical insides of modernity. Both try to replace Christian teleology with materialistic determinism, with equally abysmal results. And the struggle between the two siblings of the Enlightenment is still raging, with the outcome far from clear.

Marxism has been so influential over the past century and a half not because its home was in the Soviet Union, but because it is in the heart of modernity. Marxism in economic, social and political thought is the same as Darwinism in biology. It tries to plug a hole left by Christianity, only to find it unpluggable.

But it will persevere for as long as modernity does. In the absence of real, aromatic coffee of philosophy, a surrogate concocted of Enlightenment acorns has to do. And Marx, along with Smith, Darwin and Hayek, is one of the acorns of which that unsavoury beverage was brewed. “Marx’s teaching is omnipotent because it’s true,” wrote Lenin. It’s neither, actually. But Marxism is a systemic, untreatable malaise of materialist modernity. It will continue to fester until it kills the host organism.